It Is Time - A Paper by Dr. Harry Edwards

It Is Time

From Protest to Policies, Programs, and Progress

A Paper Summarizing the Challenges and Options faced by Athlete Activists Today

by

Harry Edwards, Ph.D.

Professor Emeritus, U.C. Berkeley

Institute for the Study of Sport, Society and Social Change

San Jose State University

May 22, 2018

Summary

Owing to a constellation of developments already well this side of the sports-political horizon, it is not only advisable but critically imperative that today’s athlete activists move beyond protests to direct participation and involvement with peoples and communities struggling under burdens of injustice. Factors compelling this shift in athlete activists’ focus and approaches have to do not only with the urgency of meeting the challenges involved, but with the inevitable dissipation and denunciation in the perceived legitimacy and constructiveness of continuing protests in the sports arena.

As succinctly put as possible: it is time for this generation of athlete activists to move beyond protests in the arena to advocacy for, support of, and participation in collaborative community efforts to craft and institute policies and programs conducive to progress in resolving those issues of injustice that have provoked and fueled protests over the six years since the Miami heat’s “hoodie protest” in 2012 in the wake of the killing of Trayvon Martin. And let me be clear – this call for a shift in strategic approach and methods has nothing to do with the National Football League’s “Social Justice Agreement” with a coalition of former and active N.F.L. players, or with its promised annual allocation of $250,000.00 per franchise to match a similar sum potentially contributed by each team’s players. Any discussion of whether that agreement constitutes a “quid pro quo” toward bringing a halt to player protests is irrelevant in terms of the arguments made here. Furthermore, peoples of color in America learned generations ago – dating back to treaties struck with Native American populations, to the agreement stipulating that “40 acres and a mule” would be allotted to each formerly enslaved family, to the first fifteen Amendments to the United States Constitution for that matter – that the “devil” is not so much in the details as in the delivery. If it turns out that the “Social Justice Agreement” is productive of its promise, it must be deemed not only a step toward progress , but perhaps even a model for other League /player issues not covered under the Collective Bargaining Agreement. At this point , any assessment made relative to what the N.F.L.- Players Coalition agreement will or will not deliver would be presumptuous and premature at best.

The basis of my arguments and conclusion, that it is time for activist athletes to move beyond protests in the arena are more considered and complex.

Since 2012, a corps of mostly Black, courageous and committed players with affiliations ranging from the professional ranks down through collegiate, high school, and even middle school athletic programs have upon occasion protested injustice in society during the playing of the National Anthem, targeting in particular the inordinate and disproportionate number of homicides committed by police against peoples of color. These protests by athletes, then, have been spawned principally by issues associated with human and institutional relations beyond the sports arena itself, issues that in effect have traversed arena walls and in this age of the internet and social media – resonated powerfully in the locker room, especially with athletes from community backgrounds similar or identical to the communities in which the police homicides have been perpetrated. These athletes have endeavored to use their sports platforms to become the “voices of the voiceless”, to send a message exposing injustice to the millions of fans who applaud, follow, and support them and their teams, to send the message that it’s time for this nation to acknowledge, to confront, to address, and to resolve these issues of injustice, and that athletes, as citizens they themselves are committed to the work of addressing and correcting these problems.

But largely by virtue of the very fact that the injustices protested have no direct “organic” or “foundation cause” within the culture, organization, or institutional functioning of these athletes’ sports, their protests have been far less amenable to evolving into collective action and, therefore, have been manifest mostly as vaguely associated protest actions focused on “outside issues” impacting communities of color. The vast majority of athletes – irrespective of race, gender, or ethnicity, etc. – have not joined in the protest efforts based most fundamentally on this reality. This has left those athletes who do protest vulnerable to both “protest fatigue” – an erosion of enthusiasm for protest due to a lack of peer support – and to isolation and adversarial retaliation in efforts to silence them and to discourage other potential protestors.

As with all protest efforts, the longer such an “individualized” protest movement persists, the greater the erosion of its intensity, its power to command attention, and most often, its impact. Individual protests more quickly reach a stage of “impotent redundancy” where even targeted audiences – adversarial and supportive – begin to lose interest. This “erosion of potency” also becomes more acutely evident because the protestors are alone or so few in number.

Owing to inherent internal contradictions and frictions, external conflicts and vulnerabilities, and, to no mean degree, even achieved successes, every protest movement – including those with committed centralized leadership and clearly enunciated goals, standards of achievement, and productive methods – come with an “expiration date” by which time they must evolve and undergo a type of “phase transition” or confront the prospect of protesters being reduced to caricatures of themselves and their movement descending into parody trending toward irrelevance.

Consider the evolution and fate of the Black Civil Rights Movement of the 1950’s and 1960’s under the capable leadership of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). This movement, like other well-led and organized movements before it, came with a prospective expiration date of ten years, more or less. (Two past examples come to mind here: the Universal Negro Improvement Association Movement – the most successful Black protest movement in American history as judged by membership and support numbers, – lasted from 1917 – 1927 before fading into irrelevance under the burdens of severe criticism of its leader and founder, Marcus Garvey – by other Black civil rights leaders and leadership organizations, and with Garvey’s eventual imprisonment and deportation in 1927; and the “Great Experiment” in Major League Baseball forged by Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey from 1946-1956 – an effort that was really this nation’s first “non-violent direct action” movement against racial segregation in professional baseball. By the time of Jackie Robinson’s retirement in 1956, desegregation of Major League Baseball locker rooms had undergone a “phase transition” from an “experiment” to the institutionalization of desegregation strategies, methods, and standards of achievement, to such an extent that neither Robinson nor Rickey were any longer critical to achieving targeted outcomes.

Dr. King’s emergence as a major civil rights figure began with his appointment as the spokesperson and leader of the Montgomery, Alabama “Bus Boycott” effort in 1955. Over the next ten years, beginning with achieving the goals of that movement, he became the face and voice of a coalition of civil rights leaders and organizations (sometimes called the “Big Five” of the Civil Rights Movement: Dr. King’s S.C.L.C., Roy Wilkins’ National Association of the Advancement of Colored People or N.A.A.C.P., James Foreman’s Congress of Racial Equality or C.O.R.E., Whitney Young’s National Urban League, and John Lewis’ Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee or S.N.C.C.) that successfully mobilized public and political pressure on three presidential administrations (Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson) and the U.S. Congress to pass Civil Rights and Voting Rights Bills, Open Housing, Fair Employment, and Equal Access to Public Transportation and Accommodations legislation, and more – all eventually leading to international recognition and honors for King, including the awarding of a Nobel Peace Prize in October of 1964. Still, less than two years later, in June of 1966, Dr. King’s leadership was under withering criticism, the Civil Rights Movement he had been so central in forging was adrift and foundering, and there was a full-scale revolt against him personally, his philosophy, his goals, his non-violent methods, and in some quarters even his message of love, peace, and tolerance. Foremost among those in revolt were less patient, more militant younger activists led by SNCC’s newly installed leaders H.Rap Brown and Stokely Carmichael who coined and popularized the proto-hashtag “Black Power!”. But Carmichael and Brown were far from alone in turning away from Dr. King. At least partially in an effort to reinvigorate the Civil Rights Movement in its non-violent, inclusive integrationist guise and his leadership of it, to reclaim the allegiance of disaffected and disgruntled younger activists, and undoubtedly out of a sincere concern over issues of war and poverty, Dr. King in April of 1967 spoke out against America’s Role in the Vietnam War, and in March of 1968 undertook to challenge the established American economic order by announcing his plans for a “Poor Peoples’ Campaign.” Both his anti-Vietnam War stance and his plan to re-cast the Civil Rights Movement as an economic struggle focused upon the poor – beginning with a proposed “Poor Peoples’ March on Washington” – were more in line with the ideology and demands of the burgeoning Black Power! Movement. On January 17, 1968 Dr. King even endorsed the Olympic Project for Human Rights, perhaps the quintessential expression to date of audacious Black Power! activism. While such actions by Dr. King did to an extent assuage the misgivings of some who were alienated from his leadership, they provoked even more caustic criticism from others, particularly from more traditional civil rights leaders and organizations. As Reverend Jesse Jackson recently recalled in a CNN interview: “In the months and weeks leading up to the Poor Peoples’ Campaign in 1968, many in political power had stopped listening to King. Longtime friends and allies in the movement turned on him, the government, the press, the Democratic Party, his fellow civil rights leaders, and Black ministers closed their pulpits to him. They told him to stay in his lane and not to bother himself with issues of War and economic justice.

But Dr. King’s concern with war and economic justice was substantially aimed at regaining leadership authority and legitimacy and re-energizing the movement, both of which were foundering by the summer of 1966 when Stokely Carmichael seized substantial control of both the microphone and the activist energies of the Civil Rights Movement with his call for Black Power!. Dr. King’s optimally effective reign had lasted for ten years. And what were the forces that pre-saged his decline as a leader?

First, the aspirations and expectations of those on whose behalf an activist movement is forged will always outstrip the capacity of the movement and its leaders to deliver – even where goals and standards of achievement are clearly agreed upon, articulated, and established. A degree of popular frustration with the movement and its leadership is, therefore, inevitable.

Second, differences in organizational philosophies and operational methods between movement interests, and differences in vision, style, competence, perspectives, and skill sets among movement leaders generate frictions and conflicts that ultimately “weather” and erode mutual collaboration incentive, trust, and confidence. Under the circumstances, corrosive criticism rather than staunch support increasingly prevails – eventually spilling into public expressions of discord.

Third, in the inexorable course of developments during the evolution of a movement, leadership mistakes are made; failures of strategy and judgement occur; changes and adjustments in methods, immediate and “down range” goals ,in the pace of the struggle , in reassessments of outcomes achieved in light of subsequent revelations are all inevitable and unavoidable; and personal and human frailties in leaders and other key personnel are to some extent suspected or exposed. And finally, adversaries become more adept and skilled at frustrating, limiting, and even reversing movement gains, while undermining support for and the effectiveness of movement leadership, often through disinformation, character assassination, persecution, and the creation of threatening and hostile protest environments.

While some activist protest organizations might manage to “soldier on” beyond the decade timeline, they typically do so in relative obscurity, if not outright irrelevance. Most protest leaders, then, succumb to the above internal contradictions and external conflicts within a decade (Marcus Garvey, 1917-1927; Dr. King, 1956-1966; Malcolm X, 1952-1963, when he was driven out of the Nation of Islam Movement).

In the mid and late-1960’s, protest leaders mobilizing under the banner of Black Power! would experience an even more rapid decline in influence and legitimacy than Dr. King and other more traditional leaders. Not only were these Black Power! protest leaders subject to all the forces cited above, forces that weathered and eroded the careers of traditional Civil Rights Movement leaders, they were also impacted by other dynamics that hastened their leadership demise still further, limiting their leadership viability not to a decade, but to only six years on the average from concept to collapse into virtual irrelevancy.

I have called Black Power! a “proto-hashtag”. As such, in 1966 it was a shouted “slogan” that morphed into a movement. It was a national movement without central leadership, without specific and clearly detailed and articulated goals, methods, or standards of achievement. As such, the movement evidenced an amoeba-like fluidity in goals, in the character of affiliated or identifying groups, in methods, and more. Black Power! as a slogan made no specific demands, only hinted at a desired state of human relations and institutional arrangements, and was open to all Black peoples’ activist protests and mobilization efforts – as long as they claimed they were an expression of or attempt to institute Black Power!

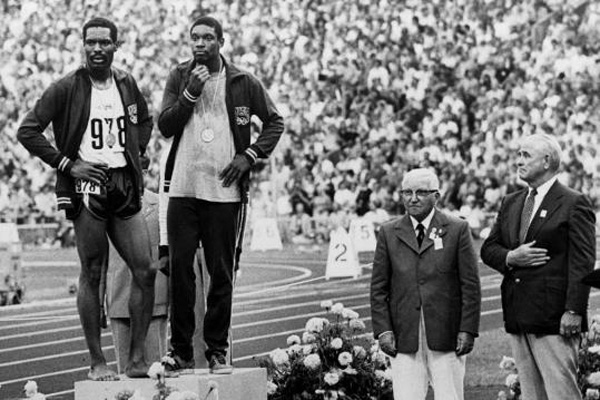

The Black Panther Party, under Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, with its attempts to create community-based support programs and its police monitoring efforts was seen as a manifestation of Black Power!. Black student efforts to establish Black studies programs and departments through taking over administrative offices and protests and boycotts by athletes at predominantly White colleges and universities between 1966 and 1972 were defined and perceived as expressions of Black Power!. The raised fist protest gesture at the 1968 Olympics by Tommie Smith and John Carlos was seen as a Black Power! protest. Black Power! had a chameleon-like capacity to become anything to any activist cause – which was both its greatest asset and its greatest liability.

Under the circumstances, the Black Power! movement spread through Black activist political culture like a new dance fad, the rhetoric of Black Power! like the latest hip slang. In short order, the intensity and momentum of the Black Power! movement weakened and waned and finally dissipated into irrelevancy under the burden of an ever expanding diversity of activist activities and causes pursued in its name. By 1972, shouts of Black Power! that had first incited Black protestors to more militant perspectives and efforts and that had engendering suspicion and distrust in the civil rights establishment while provoking anger, fear, and defensiveness in the White mainstream, were already muted and the movement was well on its way to becoming a parody of itself.

By 1972, the Black Panther Party that was inspired by the Black Power Movement, that had audaciously taken guns into the California State Legislature in 1967, that had trailed police cruisers around the Black community taking Polaroid photos during police stops, was on a mission to institutionalize and “normalize” its leadership and organization. Co-founder Bobby Seale was running for Mayor, Panther member Elaine Brown announced her candidacy for City Council, the Party gave away 10,000 bags of groceries at an Oakland city–operated venue, and the Party opened a charter school funded partially by state funds. Still, even with some success in efforts to create a less militant profile, to transition to a more traditional civil rights organization and leadership, for all the reasons and dynamics cited above – inclusive of both internal contradictions and external conflicts – within ten years, in 1982, the Black Panther Party was officially dissolved.

The Black Panther Party rose and fell twice – once under the “expiration date” and relatively more amorphous auspices of the Black Power! movement from 1966 to 1972, then under its reorganization as a more conventionally focused activist political party (pursuit of elective office, schools, community support services, etc.) from 1972 – 1982, a span of exactly ten years.

In 1972, Vincent Matthews and Wayne Collett stood atop the victory stand after winning gold and silver medals, respectively, in the 400 meter sprint at the Munich Olympic Games – and there they staged a protest demonstration during the playing of the National Anthem. By Smith-Carlos standards, it was a “casual” protest: Collett stood barefooted, hands on hips, staring into the distance while Matthews had one hand on his hip, the other on his chin as if in thoughtful contemplation of what the day might bring while waiting on a bus. But for all of the casualness of their protest in contrast to the 1968 Olympics podium protest gesture, the response of Avery Brundage – who had banned Smith and Carlos from the games and the Olympic Village – condemned Matthew and Collett to the exact same fate. The United States Olympic Committee fully supported Brundage’s actions on the grounds that the two athletes had “insulted the flag”, this despite Wayne Collett’s statement that, “I love America. I just don’t think its lived up to its promise. I’m not anti-American at all. To suggest otherwise is not to understand the struggle of Black people in America…”

Another measure of how strong the Olympic establishment’s reaction was to the Matthews-Collett protest gesture is the consequent fate of the U.S. 4×400 relay team, which was favored to win the gold medal in the event. Without its two best athletes, the team never even took the track and was disbanded, meaning that four Olympians – more even than in the case of the 1968 protests – were effectively banned from further participation in the games. And yet Matthews and Collett, their protest, and the price that they (and collaterally, their 4×400 relay teammates) paid are largely forgotten, even by those on whose behalf they protested.

It was not just the attacks that took hostage and killed 11 members of the Israeli Olympic contingent that has dimmed and shrouded memory and perceptions of the historical relevance of the Matthews-Collett protest. The 1968 Mexico City Olympics were far more violent with more than 1300 people killed during student protests surrounding the costs of hosting the game and the draconian measures taken by the Mexican government to create space for game venues. But Smith and Carlos are not only remembered – their 1968 protest is memorialized in books and documentaries, commemorated in scholarly programs, conferences, and symposia, and honored with statues, honorary degrees, and other insignia of recognition.

By 1972, the Civil Rights movement was in deep decline and had been since the death of Dr. King and the Black Power! Movement, which both framed the Smith-Carlos protest ideologically in 1968 and gave it popular legitimacy and resonance, had dissipated to the point of near irrelevancy. And so, Matthews and Collett stood in retro-political isolation on the Victory podium, protesting in a “time bubble” that referenced and recalled a Black Power! era of athlete activism which had simply expired. (Other activist athletes would follow in their wake over the next 40 years until 2012, unaware that both they and their protest efforts would be discounted, dismissed, and ultimately forgotten, e.g.; Craig Hodges, Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf, and others.). Matthews and Collett had courageously endeavored to make a statement about the realities of racial injustice and oppression in America and, owing largely to timing, had succeeded for the most part only in providing “targets of opportunity” for adversarial political interests to “flip the script” and deflect attention from the substance of their message to the style of their protest, a style that was alleged to insult the American flag. What little remained of the political profile and perceived relevance of the Matthews-Collett protest – even in Black society – was overshadowed and overrun in short order by other developments already well this side of the social-political horizon that would command interest and attention throughout the American population – including Black society.

On June 23, 1972, the U.S. Congress passed the Title IX Amendment to the Education Act of 1965 which banned gender discrimination and mandated parity in the allocation of resources and opportunities in educational institutions receiving federal funding. Then on January 22, 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed Women’s right to abortion services. In combination, Title IX and Roe v. Wade would become the foundation supports for an explosion of advancement opportunities for women – nowhere more evident than in sports. Colleges granting athletic grants-in-aid to women began the expansion from 26 in 1972 to the 539 institutions doing so today. And then there was the artfully crafted, marketed, and publicized episode of sports-political drama billed as “The Battle of the Sexes: Billie Jean King v. Bobby Riggs”, a tennis match that took place on September 20, 1973. King defeated the 55 year-old Riggs, and her victory was widely touted as a milestone achievement in refutation of prevailing assumptions relative to women’s athletic capabilities and competitiveness. By the end of 1973, there had emerged a vitally rejuvenated modern women’s movement led by the likes of established feminist figures such as Betty Freidan and rising luminaries like Gloria Steinem who had mastered the power of television and popular magazines as vehicles of mass communication. Women both in sport and beyond had seized the protest stage and National attention.

And linking the women’s movement to another constellation of developments, in 1972 Shirley Chisholm became the first Black and more importantly, the first woman to seek the Presidential nomination of a major political party. Whatever the potential perceived relevance of further athlete protests post 1972 was smothered and drowned out in the turmoil and contentiousness of that election year.

After one term in office, President Richard Nixon and his administration were under severe criticism for suspected – and in some cases demonstrable – unethical and criminal transgressions. On October 10, 1973 former Vice President, Spiro Agnew – who had resigned his office to become head of the Nixon re-election committee – pleaded “no contest” to a felony charge of income tax evasion after months of professing his innocence and attacking the press on the issue; and Nixon’s Attorney General, John Mitchell, was charged in 1973 with multiple crimes committed in association with his role in the infamous “Watergate Burglary” of the Democratic National Headquarters Office and eventually sentenced to nineteen months in federal prison. Richard Nixon himself was compelled to resign the Presidency under threat of impeachment in 1974 after audio tapes revealed that he had played a central role in orchestrating a cover up of the Watergate burglary, while all along dismissing the investigation of the crime as a “witch hunt.”

The consolidation of feminist interests and activism that fueled a modern Women’s Equality Movement and a scandal and crime-ridden Presidential Administration in the election year of 1972 overwhelmed the expression, potential effectiveness, and most certainly the perceived relevance of activist athlete protests in the arena – a situation that would prevail long after the fervor of the women’s movement had declined and Nixon had left office.

History never precisely repeats itself, but the dynamics of historical developments in a society do. As of the year 2018, this latest “wave” of athletic activism in protest of injustice is well into its sixth year, by which such protest movements have gone into precipitous decline. In short, this protest era is approaching its “expiration date” – and factors generating its impending decline are consistent with those evident in the case of the Black Power! era protests, along with some additional vulnerabilities that Black Power! era athlete activists could have scarcely imagined.

The current era of athlete activism can initially be traced to the Miami Heat’s “Hoodie Protest” in 2012 over the killing of Trayvon Martin. However, protests really didn’t begin to increase in number and merge in popular perception as connected until the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter began to morph into the underpinning of a movement in 2014 following the killing of Mike Brown by police in Ferguson, Missouri. The hashtag was created by three Black women – Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullons, and Opal Tometi – who, like the Heat players, were enraged over the killing of Trayvon Martin, but all the more so because of the acquittal of the private security person responsible. Like the “Black Power!” slogan, “Black Lives Matter” makes no demands, has no central leadership hierarchy, and no defined set of goals, methods or standards of achievement. Black Lives Matter, as did Black Power!, gradually became transformed into an ideological invention and messaging vehicle allowing for the expression of Black people’s affirmation of their humanity, of their aspirations, and of their political determination to survive and to prevail. As the Black Lives Matter Movement has evolved, it has through both its inherent dynamics and by deliberate design endeavored to specifically encompass and include all Black lives, encouraging people into the activist center influencing and guiding the movement not only traditional Black (heterosexual focused) leadership and concerns with injustice and official violence, but LGBTQ, disabled, the formerly incarcerated, and others. To quote from what amounts to a Black Lives Matter mission statement from one of its founders: “It became clear that we needed to continue organizing and building Black Power across the country. So as “Black Lives Matter” developed throughout 2013 and 2014, we utilized it as a platform and organizing tool. Other groups, organizations, and individuals were encouraged to use it to amplify issues of anti-Black racism across the country, in all the ways it showed up….soon we created the Black Lives Matter Global Network infrastructure. It is far reaching, adaptive, and decentralized…Our goal is to support the development of new Black leaders, as well as create a network where Black people feel empowered to determine our destinies in our communities.”

This statement would have been a more than accurate expression of the mission of Black Power! advocates from an era more than 40 years ago. The Black Lives Matter Movement, thus far, has not so much achieved any agenda of coherent and clearly defined and specific goods – it never had one – as it has contributed to the evolution of an inclusive popular cultural and political environment conducive to the broad scale encouragement if not incitement of protest activism. This is the movement’s greatest strength – and its greatest vulnerability. The Black Lives Matter Movement can expect an optimally influential run of approximately six years, more or less from 2013 to 2019. And there are some indications that the movement might be ahead of schedule in its dissipation and diminution as a national Black cultural and political force to be reckoned with. Its profile in both the mainstream media and the social media is a lot less prevalent than in the halcyon days and months following the deaths of Mike Brown, Eric Gardner, Tamer Rice, Sandra Bland, and Mya Hall. Black Lives Matter currently counts 40 local affiliate chapters across the country, but there are many more “woke” Black individuals who identify themselves as Black Lives Matter advocates than would ever join a chapter of the movement – just as there were far more individuals who identified themselves as Black Power! activists and advocates than ever joined SNCC, or the Black Panther Party, or even campus Black student organizations or other such groups. If history follows pattern, with no central leadership hierarchy, goals, methods, etc., the rapid expansion of the movement to include a broad diversity of affiliated and unaffiliated interest portends its unavoidable dissipation and increasing impotence. The internet and social media – with their characteristic penchant for facilitating numerous, but shallow relationships and creating fake and false narratives could hasten this trajectory toward dissipation still more. But even if the movement can weather its own inherent contradictions and external conflicts, there are two more developments that threaten to diminish its profile and its popularly perceived relevance.

There is first of all a burgeoning Women’s Movement that has arisen under the umbrella hashtag #MeToo and in response to the election of Donald Trump. In 2007, the “MeToo Program” was created by a Black woman, Tarana Burke, in response to what she observed to be the neglected support needs of women of color who had been the victims of sexual assault and abuse. But it was 10 years before the hashtag #MeToo emerged as a rallying cry that morphed into an important and highly visible emphasis in a movement led largely by affluent White women. (A contentious point of debate among participants in the 2017 Women’s March in protest of the election of Donald Trump was the representativeness of the movement and its leadership.).

As was the case with the women’s movement of the 1970’s, the 2017 #MeToo movement spearheaded by prominent actress Alyssa Milano burst into the spotlight in a “protest environment” and “activist climate” fomented and perpetuated by Black Movement activism.

In the 1970’s the political environment conducive to the rise of the women’s movement of that day (which also was led by affluent white women, e.g., Gloria Steinem and Billy Jean King) was generated and nurtured in part by the Civil Rights and Black Power! movements of the 1960’s. In 2017, the women’s movement emerged in an atmosphere primed for political protest by the Black Lives Matter movement and all of is derivative expressions – including, as occurred in the 1960’s under the auspices of Black Power! activist influences and images contributed by Black athletes, e.g. the protests of Black N.F.L. players during the playing of the National Anthem, N.B.A. player protests, etc.

For the keen observer of contemporary popular political movements, the potential of the 2016 broader women’s movement to overrun and help dissipate the “stage-setting” Black activist movements and its foundations is clear. In fact, the #MeToo aspect of the Women’s Movement has already had an erosive effect upon its first “victim” in that regard – the “#MeToo Program” started by Tarana Burke. Ms. Burke has even gone so far as to issue a warning: “Watch carefully who are called “leaders” of the movement… I don’t say much on line about what is going on with the #MeToo Movement because honestly there is so much wrongheaded chatter all the time I don’t have time to chase it all down. But, I’m particularly challenged by this framing in the media of #MeToo.” Burke went on to complain that she is “frustrated in particular with who the media has picked out as “leaders” of the movement and how that “erases” not just my work but also its original focus on Black and Brown women.

Ms. Burke, the creator of the “MeToo” concept, her program, and her leadership are all being overshadowed and overrun by the 2016-2017 Women’s Movement, a fate that awaits other Black activist movements including Black Lives Matter and the current era of athlete activism that it helped to frame ideologically and focus in terms of targeted issues.

A second force that promises to overshadow and overrun the Black Lives Matter Movement and its component athlete activism – thereby diminishing perceptions of the influence, impact, and relevance of both – is the fact that 2018 – like 1972 – is an election year. And again, there is a Presidential administration in power that is virtually under siege, all the while claiming a “witch hunt” is being orchestrated by federal investigators, the media and Congressional committees under the pretense of investigating unethical and criminal transgressions that might extend all the way into the White House and the Oval office. As these inquiries and investigations begin to conclude over the next two years, they will overshadow any and all other political activity, save perhaps a declaration of war or a response to a “9/11 level” terror attack.

In sum then, 1) since their onset, both the Black Lives Matter Movement (2013) and the current wave of athlete activism (2012) have been “on the clock” due to inherent internal contradictions and dynamics and to external conflicts and both are approaching the historically demonstrable limit of six years within which such popular political protest efforts have been able to sustain their movement coherence, energy, legitimacy, and command of popular attention; and 2) that both movement efforts are likely going to be overshadowed and overrun in the immediate future by larger, more sweeping political developments in the realms of both protest politics (the Woman’s Movement) and more conventional politics (the 2018 mid-term elections which are likely to be inflamed by on-going inquiries and investigations into alleged ethical, civil, and criminal misconduct at the highest levels of the executive branch of government).

There is also the further consideration that the accessibility and power of the internet and social media and the consequent associated vulnerabilities are currently beyond the competences and capacities of activist individuals or movements to either eliminate, control, or effectively manage in their interests or to their advantage. Already, there is evidence that some athletes’ protests have been targets of disinformation, perception management, and “photo shopped” images calculated to inflame opposition and sow greater controversy, confusion and division among the various parties to the debate over the focus, style and venues of athlete protests.

And then, there is this question: what and who are protesting athletes messaging? At the opening of a recent lecture, I asked a mostly White audience of over 450 people, “How many of you feel somewhat uncomfortable, uncomfortable, or highly uncomfortable with the protests of athletes during the playing of the National Anthem?”. About three-quarters of the audience raised their hands. And then I asked “How many of you would trade places with Black people in America today?” – not a single White hand was raised!

So if the primary targets of athlete protests against injustice are the White Majority and a justice system that works principally on their behalf, it would appear that Whites are already well aware of the inequities suffered by Black people, and so much so that they would not want to trade places, with them. (I would encourage activist athletes in particular who are afforded the opportunity to speak before substantially White audiences to ask my two questions of them – their responses are typically cravenly “cringe worthy” in their contradiction). Such audience responses make it clear that many perhaps find the venues and platforms used to stage protests – sports events during the playing of the National Anthem – more objectionable than the unjust conditions and circumstances of Black Americans (and other peoples of color), circumstances and conditions so severe and unacceptable that White people for the most part would not want to trade places.

So given all that is already demonstrably evident, what could possibly justify the continued risks and sacrifices associated with the courageous, deeply appreciated , but increasingly less productive acts of protest taking place on the playing field or court, or other forms of protest actions- such as not taking the field or court at all- during the playing of the National Anthem?

One development , however , will extend the viability of this declining protest movement : the imposition of ill-advised League regulations concerning protests during the National Anthem that promise nothing so much as to inflame the situation. The option of players staying in the locker room is destined to backfire : it will disrupt team unity and routines involving taking the field together and in some instances the practice of announcing starting player introductions ; it will put an even bigger spotlight on players who are not on the field during the Anthem ( and raise questions even about players who might be in the locker room for non- protest reasons); the fines levied against teams where players choose to take the field and protest during the Anthem anyway will create a bigger spotlight on protesting players than ever ; to the extent that the new regulations do have a substantial impact , they will create yet another “tension point” involving disciplinary issues between franchises and the League office and between players and their teams ; and it perpetuates the fallacy , the outright fiction that player protests have been waged out of disrespect for the Anthem and the flag . The new regulations promise to transform players’ activism from an externally focused protest against injustice in society into an internally focused football issue involving a clash of ( mostly African-American) player rights with (overwhelmingly White ) League and ownership disciplinary power , especially since the new regulations realistically target principally players (how does the League’s “Anthem police “ identify the dozens of non-uniformed franchise and contract employees ) who might also be on the field during the Anthem . In this off-season, people -not even players -were talking about player protest beyond the Kaepernick and Reid law suits. The actions of the League in instituting anti- protest regulations have essentially put a dying movement on LIFE SUPPORT . The first rule of managing inflamed development is “ First do no harm”, don’t throw fuel on the situation. It’s a sad, sad individual ( or League) that will only learn through personal experience..Sometimes- this time – the best policy is no policy at all.

It is time for all parties involved to both “beat the clock” and get out ahead of the dynamics that history tells us are already well this side of the sports-political horizon. It is time to move on from a focus on protests to the formidable task of working directly with the people in their communities, with helping to craft policies, develop programs, and set standards of progress. It is time to move protesting, speaking, and otherwise messaging about the people and their circumstances to standing and working directly with the people and whatever other interests or potential allies that might be earnestly willing and committed to working with dedicated athlete activists in achieving the goals of greater justice for Black people and other peoples of color and their communities. It is time for all players who have protested in the past and who still desire to play to be invited to preseason camp NO QUESTIONS ASKED, NO CONDITIONS IMPOSED. To deny such opportunities , to insist upon some humiliating-and probably illegal- a priori forfeiture of “ First Amendment Rights” as a condition of these players resuming their football careers would accomplish nothing so much as inflaming the situation and sustaining media and public focus on the “ martyrs” of a movement that would otherwise continue in precipitous decline. And still, all said, it is imperative that all parties to this situation be cognizant of the lessons of history: even if we are successful in “turning the page”, in instituting a “phase transition” by pro-actively moving beyond protests toward progress, we will still be “on the clock”, as all activists and activist movements have been. It is time for everyone who is truly serious and committed to the tasks at hand to get busy… and don’t look back – something is gaining on you: It Is Time!

May 24, 2018